Many years ago, my father

intrigued me with a story of our family secrets – tracing back to a young girl

from Hereford and a “foreigner of Jewish origins.” Needless to say, when I started to undertake

a study of our family stories, this one I had to figure out! The genesis of the legend can be found in a

memoire recounted by Beresford Day Davies (dated October 6, 1985). Beresford’s story is also interesting and

shrouded in even more family shame and secrecy, but that is a story for another

time. Beresford talks of how his father, Edward Futcher Davies (1881-1936) was

the son of a hatter, who was himself the “illegitimate son of a young girl who

came to London from Hereford and had a liaison with a well-to-do foreigner of

Jewish origins.”

|

| We are not amused by bastards! |

It’s probably worthwhile

to describe what England would have been like for the bastard son of a Jew in

the early- to mid-1800s.

Queen Victoria took the

throne of England in 1837 to 1901. The United Kingdom was a well-entrenched

constitutional monarchy, which became more so as Queen Victoria’s reign

continued. As a result, Queen Victoria’s

power came from the moral influence she could exert on the population, and she focused

on “family values”. Victorian England is

therefore known for its strict moral standards.

Being a bastard in this era was, needless to say, less than acceptable,

and the law didn’t help.

Victorian England’s

Bastardy Clause focused on punishing the mother and absolving the father of any

responsibility. The intent was to

dissuade loose women from sexual liaisons out of wedlock. This had the predictable effect of sending

unwed mothers into lives of poverty at workhouses, and their children to suffer

along with them. Unwed mothers were

scorned by Victorian society, and their illegitimate offspring ostracized.

I found it interesting

that the father in our story was described as of “Jewish origins.” Jews had

been in England since the Norman Conquest of 1066, and tolerance and discrimination

had waxed and waned in the centuries since.

By the mid-19th century, while still relatively unknown to

most British citizens because of their small population, Jews found themselves emancipated

and were allowed to sit in Parliament. In fact, it seems that being an unwed mother

or a bastard was considered far more offensive in this relatively religiously

tolerant society than being a Jew was in most of the rest of Europe.

To find who the young girl

from Hereford was, and perhaps even to find the foreigner of Jewish origins,

first I had to find the hatter that was their son. To do

that, I had to find Edward Futcher Davies.

I soon discovered two men by the name Edward Futcher Davies: Junior and

Senior. EFD Jr. (1881-1936) was the

father of Beresford Day Davies (to whom the memoire is attributed). EFD Jr. lived his whole life in London, and

was a bank clerk, beginning his occupation sometime before his 20th

year.

In 1901, EFD Jr. was

living with his father and mother. EFD

Sr. (1848-1926) was working as a silk hatter. EFD Sr., according to Beresford’s

memoire, was “rather withdrawn in family circles.” This was attributed to the fact that he was

the “illegitimate son of a young girl who came to London from Hereford and had

a liaison with a well-to-do foreigner of Jewish origins.”

Interestingly, I have been

able to trace EFD Sr.’s father, who was a French polisher named Edward Lane

Davies (1825–1902). He was married to

Susannah Futcher, EFD Sr.’s mother. So

the father here is not unknown, and Susannah is from Shoreditch in London (not

Hereford). Maybe it was Edward Lane

Davies’s father and mother that were the cause of the family secrecy? This is where my trail gets murkier, but I

can certainly, based on evidence, construct the following story that makes some

sense from the facts that I have discovered.

The Story of Edward Lane Davies

Sarah Davies found herself

quite alone when she gave birth to her son Edward in 1825 in Shoreditch,

London, England. No father was listed on the birth or baptism records, so baby

Edward started his life as a bastard.

Victorian values were strong, and an illegitimate child to a young

mother would have been nothing more than a burden. While Sarah may have tried to make a life for

herself and her son, she had no chance of seeking any help from the

father. The poor laws were against her.

|

| St.Luke's workhouse circa 1830 |

Eventually, her son, and

perhaps even Sarah herself, needed relief from the poverty in which they found

themselves. The nearby St.Luke’s

workhouse offered shelter, but this was coupled with demanding conditions. For a poor family, though, the workhouse was

the only way that Sarah could guarantee that her only son Edward received the

necessities of life, and some semblance of an education.

Living in the workhouse

meant that Sarah saw her son very little, and contributed even less to his

upbringing. She knew that her choices

were limited, and her son’s even less so.

The workhouse at St.Luke’s became their home, though they were mostly separated

from one another.

When he was a teenager,

Edward left the workhouse to fend for himself.

His life in St.Luke’s had been regimented, and life outside the institution

offered a freedom he didn’t know he could have.

|

| Ironmonger's Row is just around the corner |

In 1841, Edward, as a

fifteen-year-old, was living with a number of others, mostly men, on

Ironmongers Row in London, quite near St.Luke’s. There, even without a trade, he could get by

on his own. His mother Sarah, to whom he

had never been close as a result of their separation in the workhouse, was no

longer a part of his life, and she never would be again.

In his 20s, Edward renamed

himself Edward Lane Davies, to create a new persona perhaps, one that captured

his birth mother, but also represented his desire to be something more than his

accidental birth. He was, perhaps, imagining his

birth as one that did not come with the title “bastard”.

In the late 1840s, Edward

Lane fell for Susannah Futcher, from Andover in Hampshire. As one

of 11 children, and the oldest girl, Susannah was sent to London to find work to

help support her father, William Futcher, a sawyer. Like Edward Lane, she was seeking escape. Edward and Susannah soon found each other while living in the

poorer parts of London, and shortly after had a son, whom they named Edward

Futcher Davies. They moved in together,

unmarried, to an apartment at 11 Charles Place in Shoreditch, London.

Watching his grand-child

being raised outside of a Victorian family unit didn’t sit well with William

Futcher. He travelled from Andover to

insist that Susannah and Edward marry and raise their family properly. They did, at the parish church at St.

Leonard’s in Shoreditch on January 30, 1853.

The curator, Mr. Attwood, recorded the marriage. He turned to Edward to find out the name of Edward’s

absent father, and Edward, facetiously, replied “Adam”. Mr. Attwood dutifully recorded the name until

he realized that Edward was referring to the human male of biblical origins,

and crossed the name off in exasperation.

With that, Edward and

Susannah began their legal union. William

Futcher, in an effort to ensure that his daughter and grand-child had as

comfortable a life as possible, set Edward up with some of the craftsmen who

received the planks that William prepared as a sawyer. They trained Edward as a French polisher, and he would bring their custom cabinetry to a fine finish suitable for the homes of the

upper classes.

By 1861, Edward and

Susannah had two sons. Edward Futcher

(Sr.), at age 13 had already left school and was an errand boy, helping to

support his family. Thomas Lane was just

two years old. Edward Lane never talked

to his children about his up-bringing in the workhouse. His life with Susannah and his work in a trade

was what his children needed to know and what would keep the dark stain of bastardy away from his progeny.

Edward Futcher Davies Jr.

left home before the end of the next decade, marrying Annie Cole in 1871 and

working as a silk hatter.

By 1891, Edward Lane

Davies had lost his wife Susannah and moved in with his second son Thomas, now

working as a sanitary inspector and himself married with a four-year-old son.

Edward Lane Davies, born a

bastard in Victorian England, living independently, finding love on Ironmongers

Row, and a trade as a French polisher, died on August 16, 1902, aged 77

years. In his later years, he would tell

his son Thomas hints about the story of his humble roots. This story has changed over the

generations. Perhaps Edward Lane imagined that his father was "well-to-do", and the hint of mystery that came with "foreigner of Jewish origins" made the whole story less unseemly. So, while we don’t know the

foreigner of Jewish origins, we do know that our ancestors were scrappy, and

sought to make something of a life that would have doomed many to failure. I like to think that tenacity is the legacy of

Edward Futcher Sr., the hatter, Edward Lane Davies, the French Polisher, and

Sarah, the girl who fell for a man who left her and her infant son to fend for

themselves in the workhouses of London.

Sources:

I am

absolutely certain about the facts up to and including the year and location of

Edward Lane Davies’s birth. I found a

birth record for an Edward with only a mother (Sarah Davies) listed. The name, date and location are all consistent

with ELD, and the fact that there is no father listed is consistent with the

family story. There are no other records

that I can access until Edward Lane is 15. An Edward Davies shows up on the

census of 1841 living on his own in Saint Luke’s Parish at Ironmonger Row,

right beside Saint Luke’s, which was a workhouse. It is not too much of a stretch to consider

that the workhouse guardians would send their wards out close by once they

became teenagers. The records for Saint

Luke’s residents for the time period Edward would have been there are not

accessible to me from my armchair. I am absolutely certain of

the marriage to Susannah Futcher, and the marriage record does show Edward Lane

Davies’s father as Adam, with the name scratched out.

Updated October 5, 2015:

I have found a Shoreditch workhouse record with our Sarah and Edward listed. It seems certain now Sarah started out her new family's life in the workhouse. This is a workhouse record. The columns are: name_age_ward_date admitted (year is 1825)_date discharged_remarks. There is Sarah with her newborn admitted in June, baby born July, discharged the same year in August. I am not entirely certain what the remarks say.

Primary

Sources:

Census

(various)

Marriage

(various)

Birth and

Baptism records (various)

Death and

Probate records (various)

Secondary

Sources:

Bastardy and Baby Farming

in Victorian England by Dorothy L. Haller

The house

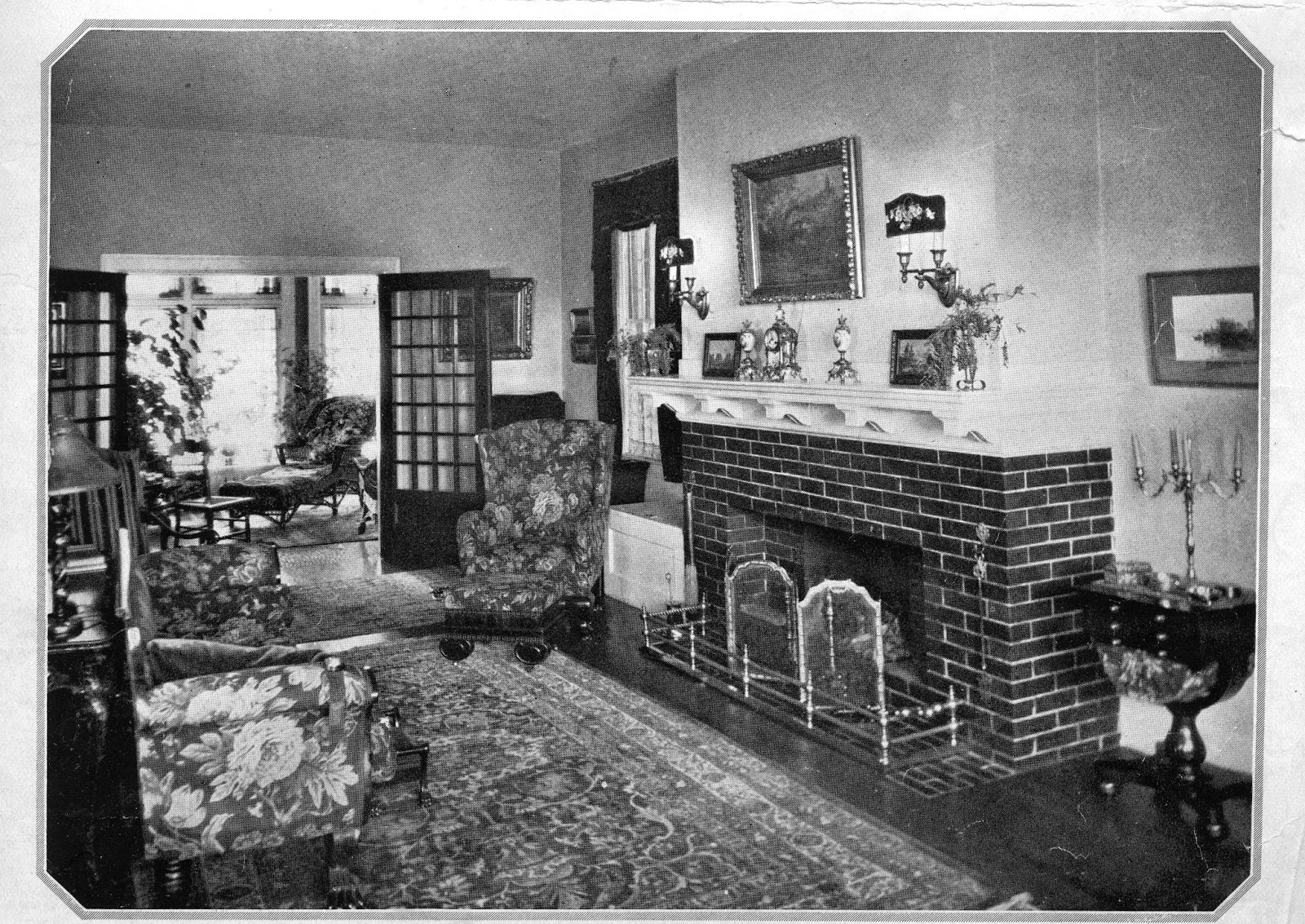

was built in the Surrey farmhouse style, and was twice featured in the Canadian

Homes and Gardens magazine. It had two

stories, with 25 rooms, including a library housing 14,000 volumes, a billiard

room, sewing room, sun room, seven bedrooms and a suite for staff. Allison heirlooms adorned the house,

including furnishings and paintings, as well as a grand piano.

The house

was built in the Surrey farmhouse style, and was twice featured in the Canadian

Homes and Gardens magazine. It had two

stories, with 25 rooms, including a library housing 14,000 volumes, a billiard

room, sewing room, sun room, seven bedrooms and a suite for staff. Allison heirlooms adorned the house,

including furnishings and paintings, as well as a grand piano.  When the

Allison family moved into the home, it became renowned for entertaining guests

in a lavish style, and notable dignitaries frequented the residence when they

came to Saint John on business. The family

lived in the house for 16 years, during which time Walter’s father Joseph died

(1924), and Walter’s business prospered.

Walter, Frances, Joseph, and Helen, lived in relatively

grand style at Woodside. The family also

enjoyed the presence of a clever yellow Persian cat named Skippy.

When the

Allison family moved into the home, it became renowned for entertaining guests

in a lavish style, and notable dignitaries frequented the residence when they

came to Saint John on business. The family

lived in the house for 16 years, during which time Walter’s father Joseph died

(1924), and Walter’s business prospered.

Walter, Frances, Joseph, and Helen, lived in relatively

grand style at Woodside. The family also

enjoyed the presence of a clever yellow Persian cat named Skippy.