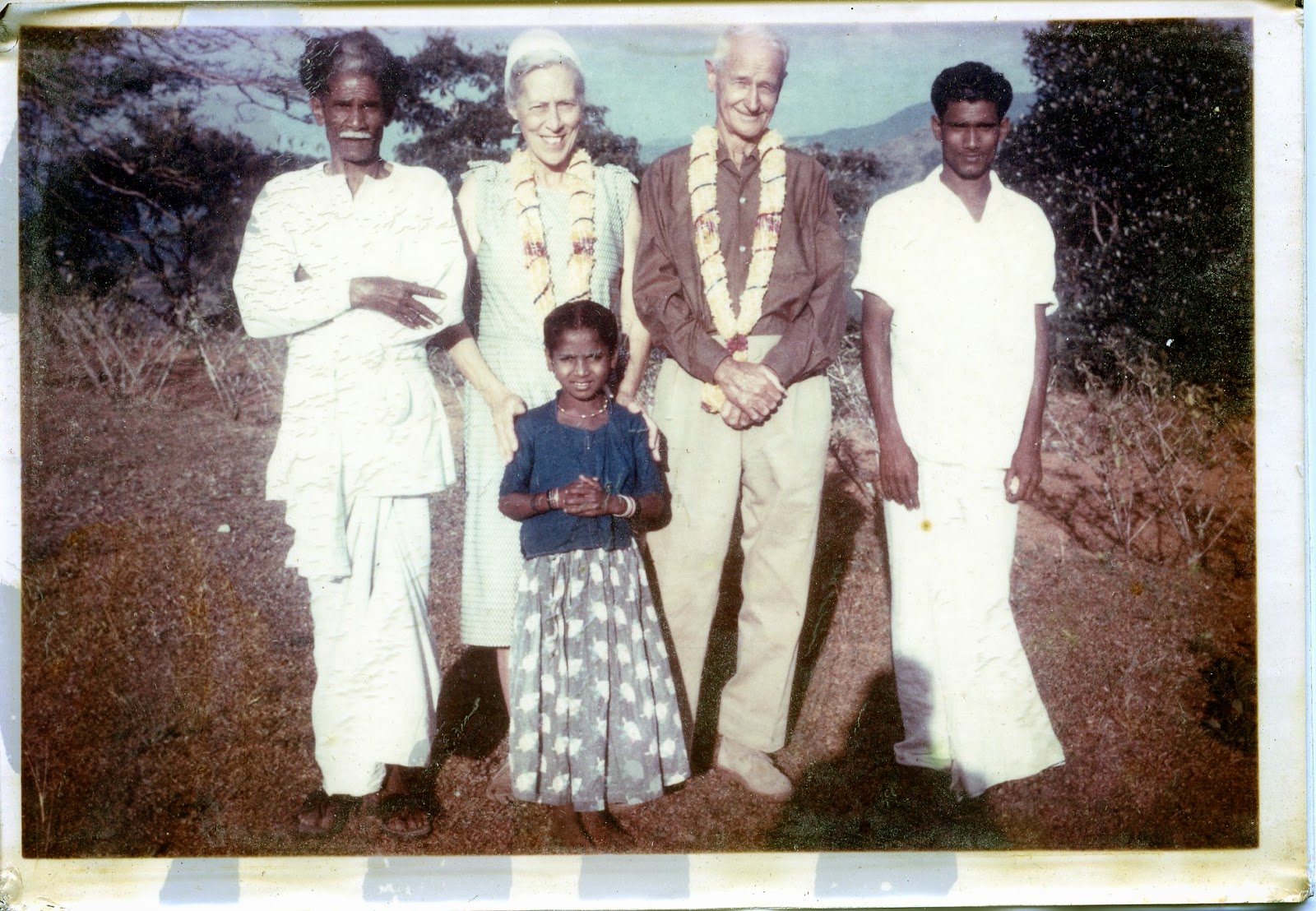

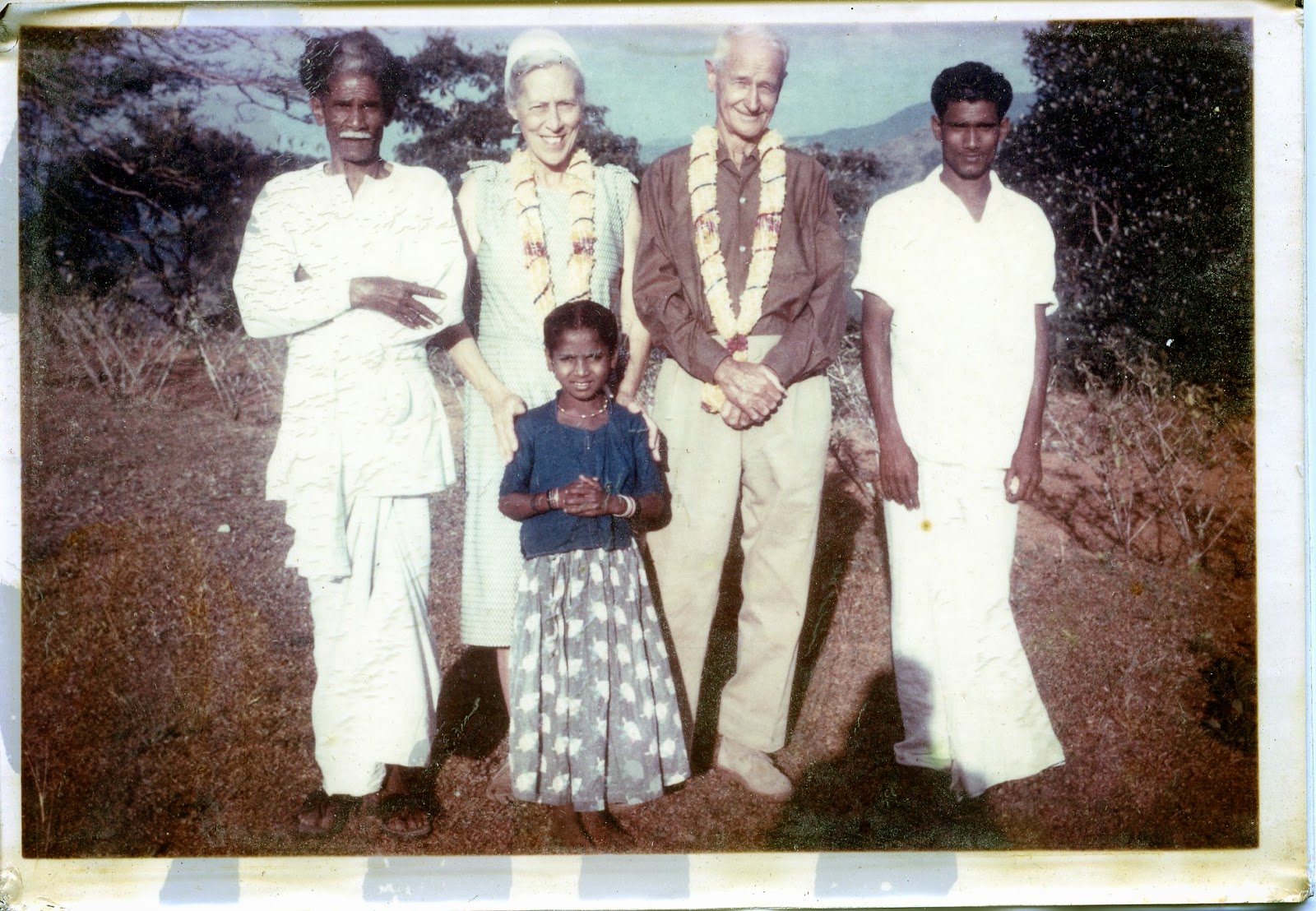

I came across a journal written by my delightfully adventurous grand-mother Isobel Maxwell. Her second marriage was to Jeffrey Wilkie, who ran a tea plantation in India. Upon retirement, he and Isobel needed to escape the Scottish winter and find a new part of the world to explore. At some point later in life, Isobel started a journal with poetry, memories and imaginings. This is the story, from Isobel's journal, of how she and Jeff (or J. in her journal) came to Africa. It is the beginning of a love story with that continent. I now know how I will answer when next someone puts to me the question: "If you could meet anyone who has died, who would it be?" I would undoubtedly now answer: "My grand-mother Isobel!" You shall see why.

|

| Isobel and Jeffrey Wilkie in India |

(I never

dreamed) Almost by Accident

“I couldn’t

possibly – I wouldn’t even know how to begin.”

“That’s

easy,” the man said, “get some paper in front of you, pick up a pen and – start

writing.”

That’s what

the man said.

The first

book I remember clearly is “Jock of the Bushveld” which was read to me before I

could read it for myself. Sir Percy

Fitzpatrick’s classic is not only the story of a man and his dog, but also of

the early days in the Transvaal where the far-sighted President “Oom” Paul Kruger created a sanctuary for the presentation of some, at

least, of South Africa’s wonderful wild life.

The Kruger

National Park covers almost 8,000 square miles.

It sounds and is terrific. At

Lookout Point, one of the few places in the Park where it is permissible to

get out of your car, we stood on top of the small hill, and in every direction

as far as the eye could see stretched the Kruger National Park, apparently

flat, uninhabited and uninteresting from that height. It was like standing on an upside –down

saucer; and I saw for myself that the earth undoubtedly is round. Not that I ever doubted it. I am more than willing in such spheres to

accept the findings of my much elders and betters. It is not the shape of the world that bothers

me, it is the condition of it.

In its present comparatively sophisticated state, the Kruger Park might hold

little appeal for the ghosts of Jock and his master. The sun shines as it

always did, and the land is still there, with wild life in plenty, in spite of

the depredations of poachers and their evil employers, and the idiocies of some

of the visitors.

The poaching

activities have at least a motive, however bad.

But it is impossible to understand, for example, the mentality of two

European tourists, who, in defiance of Park regulations which expressly forbid

this, drive their Wolkswagen off the road to within a few yards of the

lionesses on a kill. They then proceeded

to pelt the animals with potatoes they had failed to consume while camping near

the Park. That there should have been a

surplus of Kartoffeln was in itself

a mystery, but that grown men who had shown enough interest and initiative

to go camping in a country such as Africa – and there is no other such – should

have been so ignorant as to fail to realize the danger to themselves as well as

the trouble their senseless action might cause to others, is beyond

comprehension. The pity of it is that

the lionesses were apparently not interested in trying a mouthful or two or raw

tendon. Understandable perhaps.

Apart from

the annoyance caused to perfectly respectable, law-abiding lions at their own

self-supplied dinner table, what is so infuriating about such witless behaviour

is its possible effect on other visitors.

The stupider ones may well be tempted to emulate the lion baiters until

the victims do eventually turn on their tormentors. A terrific uproar, human and animal, ensues,

and certainly the roar of an enraged lion once heard is never forgotten. Some of the public will then be on the side

of the lions, and others will no doubt waste their sympathies on their damaged,

possibly deceased, human brothers; they will always be brothers rather than

sisters if only because most women can’t hit a bandorrat three feet with any

missile, so that their efforts even if they made them would pass unnoticed by

the lions anyway. In any case, it isn't

generally in the nature of a woman to tease animals, other than perhaps the

male humans occasionally.

Something in

the foregoing reminded me of twenty-twice-told tale of the Roman matron who took

her little daughter to the games at the Coliseum when Christians were being

thrown to the lions. “Oh look, mummy,”

cried her fair-minded little offspring in distress, “that poor lion hasn’t got

a Christian.”

Had the

Kruger lionesses decided after all to vary their diet, I scarcely think what

they got would have been Christian either.

Strangely

enough, no accident resulted from the potato-throwing episode but there was a

sequel.

As well as

the regular and, of course, inadequate number of salaried game rangers and wardens on the staff, there are also a number of honorary game rangers. These are often, some of them, retired from

professional employment, who, because of a deep and often unacknowledged love

of the Park and its denizens, act as guide-drivers to parties visiting the

reserve. Their interest in and affection

for the Park seem more often than not to be allied to a natural talent for

story-telling, and they never lack for material - comic, tragic, thrilling and

always fascinating – assuming of course that wildlife interests you.

By great

good luck (my feelings on the subject are obviously not impartial) the potato throwing competition was

interrupted by the arrival of two of

these stalwart characters, each driving a complement of goggle-eyed tourists. For official action to be taken, such behaviour

must be reported by two independent witnesses.

Words were exchanged, the licence number of the car was noted, some

pretty terse instructions were issued to the offenders, and on returning to

camp, the matter was reported through official channels. I am not by nature vindictive (or am I?), but

I am delighted to be able to record that the culprits were hauled before

authority, who imposed thumping fines of, I believe, 60 pounds per potato-thrower, which must have worked out quite expensively per potato. Better still, they were also forbidden to the

Park for all time. Perhaps they are now

reduced to chucking naphthalene balls into the lion enclosures of some

zoo. But there are more keepers per

square acre in zoos than there are rangers per many square miles in game

reserves, so perhaps they have been forced to relinquish their weird pastime

and are now eating out their frustrated twisted souls in some quiet cell – or

cells.

Incredible

through it may seem, naphthalene balls thrown in the enclosures did actually

cause the death of two beautiful polar bears in

_____ zoo. What unspeakable

things we humans do. Whatever, in fact,

shall we think of next?

Never while

“Jock” was being read to me, nor later when I could read it for myself, not

even when I was reading it, or more often “telling it” to my own small sons (-

“Don’t read it, Mummy – tell it! Tell

about Jock and the tableleg!”), - not at any time did I ever dream that one day

I should have the incredibly good fortune, the privilege and the indescribable

happiness – (because that is how I feel about it) of visiting Jock’s country

and seeing some of the wonderful wildlife that he and his master saw in

earlier simpler times. And when it did

happen, it happened almost by accident.

“By the way,

J., how about taxes if you go back to India next year?”

J. suddenly

looked like an imitation of a horse showing the whites of its eyes, and I sat

up with a jerk.

“If we go to

India” What on earth do you mean?” I exploded,” We are going to India – we’ve

got passages. We sail on January 4th!”

J. frowned

and ignored me. “What d’you mean Jack? I’ve paid my taxes,” he added with a

grin.

“– Albeit with the greatest reluctance and considerable resentment,” I

interrupted.

My brother-in-law

also ignored me.

“Well, you

haven’t been non-resident very long – two years? Or three, is it? Might be

safer to check up.”

And

regrettably he was right. He often

was. If we showed as much as a nose in

India for even a day within five years of leaving it as residents, we ran a

definite risk of being required to pay full taxes to the Indian government,

having already performed a like service to the British one. That seemed to be a pretty silly way of getting

rid of money even if we could afford it.

So we cancelled our passages and gave up all idea of visiting India for

the time being.

I was

bitterly disappointed and J. was exasperated.

“All right,”

he announced finally, “it can’t be India but we are going somewhere –

somewhere,” he added, “where there is a risk of too much sunshine rather than

too little.”

“Where, for

example?” I asked, and without a moment’s hesitation he went on, “We’ll go to

South Africa.”

At this

point game reserves were not even mentioned.

J.’s chief idea then was not only to escape some of the very healthy but

pretty rugged weather we can be called upon to endure between January and April

– a conservative estimate, this – on the east coast of Scotland, but also to

store up peak period heat in anticipation of the kind of summers which often

follow, and which can be almost as exasperating as the winters if you are that

way inclined. After just a forty

consecutive years in India with only rare leaves (times have changed in this

respect as well as in others) and those never in winter, my husband is

undoubtedly that way inclined.

Why do we

live here? Very simple. We like it. Which doesn’t mean that we cannot bear to

leave it from time to time on a strictly temporary basis.

Once the

decision to go was taken – and there had been no argument about it – the

question was where in South Africa? One

name was mentioned in two talks and there was no argument about that either, no

consultation of maps, not even consideration of costs. We would go to the Kruger Park and this we

did, not once, but repeatedly over the years.

We visited a

number of widely-separated places on that first trip. Trying vainly to get a

bird’s eye view of a sub-continent so vast that not even a fleet of

passionately curious could in months scan more than a fraction of it.

Each year we

hear that yet another and another game reserve has been created, until one

almost wonders if this splendid idea is not perhaps getting a little out of

hand. But there is an incredible amount

of room in Africa, - not all of it suitable lebensraum for humans – and the

prospect of too many reserves is preferable to the reverse. It is encouraging to know for example that

white rhinos, which were so recently in danger of complete extermination, are now

numerous enough in South Africa to be

exported to other parts of the continent where they once abounded. White rhinos aren’t of course white at all,

though I think that they look blonde by comparison with the decidedly more

brunette-looking black rhinoceros, which isn’t really black.

Each time we

returned to Africa, we try to visit a reserve new to us, as well as revisiting

such favourites as Hluhluwe and Charters Creek, both in Zululand. Each reserve is different and all are to us fascinating.

We set out

in thoroughly conventional fashion, with lots of luggage – ships were very

‘dressy’ in 1955 – plus golf clubs, tennis racquets and a bulging case of music

and related equipment for me to play with.

In fact I cannot think of anything less like the types we

eventually became.

J.

unwittingly took his tapestry work since I had taken the precaution of

secreting it in the luggage. But he

refused to be seen “sewing” until he was lured into conversation with a

pleasant, portly gentleman who each day on deck could be seen tranquilly

stitching away between bouts of deck games or visits to the bar and swimming

pool.

The only

unconventional part of the expedition at that time was that we had no return

passages booked for the very excellent reason that none was available. What did surprise us a little was that before

being allowed to book accommodation for the outward passage, we were asked – nay! we were required to sign an agreement that in the event of no sea passage

homeward being available, we could accept air passage. It was a little unflattering being made to

feel that our permanent presence in South Africa might not be considered an

asset, and we caught a faint glimpse of what the unwanted suffer. There was another reason for our discontent: I

am not entirely reliable in rough weather at sea but I am much less so in the

air. Sometimes all goes merry as a

marriage tell, but I have vivid and shaming recollections of my uninhibited

behaviour in flight over the Nilgiri between Cochin and Madias, and other

occasions my unfortunate spouse had to bear my brunt. There is so little privacy in an aircraft,

particularly the smaller types, and one suffers for other’s sufferings in the

full glare of publicity. In my case, the

size of the aircraft does not necessarily make any difference. There have been times in the past when I have

incurred the pained and surprised displeasure of stresses by managing to feel

quite peculiar even in some of the transatlantic monsters. I receive so much sympathy on these occasions

from my dearest, who is usually my nearest, that I can only assume I look as peculiar as

I feel. My first flights were made oddly

enough in the early thirties in small German aircraft carrying, as well as I

can remember, ten or twelve passengers.

I believe this long commercial fleet was later converted into light

bombers with no bother to the Germans and considerable discomfort of other

people’s. It gives me a useless sort of

satisfaction that on these flights at least, my behaviour was impeccable. If Germans would remember, it would perhaps

be easier for some of my generation to forget.

“You aren’t

taking any chances on having us as immigrants, are you?” I murmured gently and,

I thought, jocularly, to the member of the South Africa House staff with whom

the transaction was being concluded, as J. signed on the various dotted lines.

This wholly

friendly sally was greeted by a rather suspicious look and an uncertain half-smile. South African government

officials, I found later, are in general inclined to take themselves pretty

seriously until the atmosphere has been carefully tested and tactfully

thawed. However, this attitude is by no

means peculiar to South African officials who are in the main unreservedly

friendly, helpful and delightful people.

Early in

January, we departed with no fanfare but in great, if outwardly suppressed, excitement. We went happily on board to inspect the

ship, our quarters, and our stewards, who, as well as wrestling with the baggage,

were of course inspecting the passengers and drawing their own expert

conclusions, which mercifully perhaps they did not reveal to us just then.

Stewards are

an interesting study, and many and varied are their personalities and

techniques. We have known many excellent

ones, and we have also had one example of a different fraud/trend. In fact our first contact with a steward on

our first trip to South Africa taught us a lesson we did not forget. It transpired later that he had no right to

be in our part of the ship at all, and I am not sure that he even was a

steward, although he was dressed as one – a pretty scruffy one. All except one of our fairly numerous pieces

of baggage were brought to the cabin by miscellaneous porters, aided very

slightly by this one large untidy toothless individual in a grubby white

jacket. With much ado about practically

nothing, he had made two journeys, arriving pantingly the first time with the

smallest of our cases and on the second time with one set of golf clubs – of

about 7 clubs. On both occasions he

spread a powerful aroma which was unmistakably part beer, mixed perhaps with

gin, vodka, a dash of meth and a dish or two of mandrake juice.

“Is that the

lot, M’m?” he suggested with an ingratiating smile.

“No – not

quite – one set of golf club to come.”

“OH my then!

Oh dearie me, M’m! I’ll have to see about that, won’t I, M’m?”

“Pray do,” I

murmured, turning my head strategically from another wave of highly inflammable

fumes.

We set about

unpacking. Sailing time drew near and

still no golf club. Just as we were

thinking of ringing a bell or two, the odiferous one reappeared – more

odiferous if anything – complete with the missing golf bag and with a smug air

and an exaggeratedly triumphant smile.

“There you

are, M’m!” Then he waited for what he obviously thought was his due. But was it? J. and I looked at each other

uncertainly, and then provided

Thanking us profusely, as well he might, our friend took himself off at

top speed and was no more seen.

When our

heads had cleared a little, we came tardily to the conclusion that he had

stashed away the missing item in order to produce it at the right psychological

moment. We felt pretty stupid, but how

sweet was revenge when it came a year (or two) later.

Whether we

looked stupider than we really are, or whether he just had a bad memory for

faces we never discovered. But we were

ready for him the second time. It was

the mixture as before, fumes and all.

The missing item this time was my hatbox, which I am sure he found

heavier than he expected; it rarely contains hats. It was eventually produced almost at the last

moment – he really hadn't much originality – and he waited confidently. With a nasty smile, I said sweetly, “We have

met before – remember?”

He didn’t

even try to remember. He took my word

for it and he fled out of the cabin like a scolded cat. Nor have we met again. Maybe he was a docker in disguise and he may

have been too busy drinking.

The first

hurdles negotiated, we then settled down to enjoy what was to be, had we but known

it, the first of many journeys to Africa.

Passengers,

being people, are always a mixed bag. I don’t know into which category we fell

except that we were definitely among those who enjoyed the voyage.

At Waterloo

we had furtively examined the assembled multitude, wondering which ones were a

future shipmates and which merely see-ers off, and deciding they were a jot lot. They, meanwhile, were arriving

at similar conclusions. Once on board,

we did what most passengers do for a day or so – treated the other passengers,

when they gave us the chance, with great reserve, lest we be enthralled too

soon and too deeply for eventual disentanglement; and we ignored the occasional

mute expressions of polite incredulity that we could possibly be on board

“Haven’t seen those two before – they don’t usually “travel” do they,

dear?” I thought of Mrs. X, the Charlady

in “Outward Bound” (Sutton Vane) who, in answer to heavily sarcastic query, answered earnestly in rich cockiness “Oh yes, dear, I do, dear – every day, dear. Lambeth to the Bank and the Bank back to

Lambeth.”

Then the

edges began to crumble pleasantly and the usual but not necessarily accurate

signals began to flash: “Watch him – he’s a menace – tries to cheat at deck

games,” – (there’s usually one) and “Whoops! Take cover – she’ll talk your head

off,” and of course, “you needn’t worry about him unless you want to sit up at

the bar” as well as the inevitable “bait for junior officers” who luckily seem

usually able to cope. And shortly we

began to know which ones we’d find crashing bores, and which ones would be good

companions for the duration of the voyage and who would then vanish without a

trace or regret on either side. And a very few are right for lasting friendships; and this too we had.

Our luck was

well in on that first voyage. We found

two kindred spirits, rather, they found us.

The female of the species sought me out that we might do battle in one

of the sports competitions. That was the

only ‘battle’ we have fought in twelve years, although there has never been any

lack of subjects for discussion and enthusiastic argument too. On these two friends be ever blessing for

their warm hearts to which they took and have kept us, for their pride and

pleasure in Scotland, the land of their forebears, and for the love and deep

concern they have for South Africa, the land of their birth – all of this

inter-larded with humour and great humanity.

No wonder we love them.

So we sailed

on, southwards into more and hotter sunshine, delighting in it, soaking it up

in indiscreet qualities, reading, serving, chatting, working, swimming and

playing deck games as the moods took us.

I played

tombola as a child, senza soldi si confuse; it bored me then and still does. Since J., too, is completely lacking in gamething instinct, we family eschewed organized evening entertainments except for the

occasional dance and the movies. We are

a dead loss to the film industry when we

are on land – our average is about one film in six years, and then we may go

slightly berserk and see whole programme twice, which is I suppose a rather low

form of meanness. “Born Free” was our

last venture, and surely no one would blame us for being unable to tear

ourselves away from that while the national anthem was played and the staff

went home.

But a film

show on board ship is another matter. I

suppose we delude ourselves into thinking we are being offered something for

nothing (forsooth!), - the fares having been paid some considerable time

ago. So in we go, selecting very

comfortable seats in a strategic position.

If we don’t like the film, we can quite happily leave without feeling we

have wasted our money, as we sometimes feel we would have done by staying (if

all else fails, we can even stay and slumber gently). So nice for all concerned. There are always the stars to stroll under,

and my capacity for sleep at sea is universe.

Some of the

best “free” entertainment is to be had in the dining-salon. While it may not always be fashion, there is

usually something on show; and after a few days, it is possible by careful

observation to decide whether or not it is worth trying to get an appointment

with the hair dresser, without having to submit to pay for the experiment

oneself. It can be fun, and full of

surprises. Hairdressing is another

industry which benefits almost not at all from me. But I have delightful recollections of a

certain “Charles” – that at least was his professional name – who made a few

voyages to South Africa. Charles was

truly an expert with a real passion for his art. I knew at once he was unusual because when I

presented myself to ask for an appointment, he greeted me thus: “Oh Madam! Long hair! How marvellous!”

Such rapture

was not only flattering but very encouraging, since in my small experience,

hairdressers are more apt to view my admittedly lengthy tresses with

considerably less than enthusiasm plus an exasperated look at the clock.

But not

Charles. When the hour struck I was

ushered reverently – in slacks – into the chair. Except for the slacks – or in spite of them,

I felt rather as if I were ascending the throne, about to be crowned, which in a

way I was, come to think of it. With

deft fingers Charles removed the pins and other paraphernalia I find necessary to

tame the situation.

“Oh Madam!”

he cooed, “may I just work my will on this hair?”

“Yes, do

that Charles by all means,” I replied, "just so long as you remember that by 6

p.m. I shall be in the swimming pool.”

“Oh no Madam

–“ with a horrified look at me in the mirror.

I am often a bit horrified myself.

“But oh yes

Charles – with respect –“ I added politely.

“Then Madam

–“ with resignation and a slight snort “will you allow me to dress it for you

each evening? Please?”

And this he

did, whenever I presented myself, which I did quite frequently to my subsequent

embarrassment, he gladly accepted a modest present but firmly refused

payment. He did some quite wonderful

things with the material at his disposal and I was sincerely full of admiration

for his skills and his artistry.

|

| Isobel in 1928 - no doubt in slacks! |

He viewed it, draping pieces experimentally over my noble and very lined forehead. The line of my forehead probably reveals more

of my character than the ones of my palms, and they have been a constant source of

concern to my mother. I can remember

even in early schooldays how she prophesied I’d have a great crop and her

oft-repeated please “Do stop making faces dear – you’ll get wrinkles.” I did – lots of them. But they did not stop Charles – he probably

accepted them as a challenge, and succeeded in defeating quite a few.

Naturally in

spite of these other attractions, food is the most important item in the dining

salon. There we can watch the usual

percentage of passengers who find it beneath their dignity to order any of the

dishes that appear on the long menu. Perhaps

they get tired of reading. After long audible discussions with the

head waiter (“-But don’t you have any hummingbird’s langues flambes?”) they can

sometimes be seen wrestling with recalcitrant grouse or some other symbol of

the Head Waiter’s Revenge, or sweating profusely as they watch their crepes

being sugared as the ship nears the equator.

“I wonder

what they eat at home,” muses J.

“Bangers and

mashed probably.” I undoubtedly have the coarser mind, and I like bangers too. “Perhaps they don’t,” I said.

“Don’t

what?” J.’s eyes had widened slightly at Something Large sailing between the

doors.

“Don’t eat

at home. Bet she can’t cook.”

“Don’t be

catty dear. More wine? Good, isn’t it?”

It was.

One day

slides unobtrusively into the next as the bow pushes firmly into seas mainly

composed of navy blue satin, decorated from time to time by flights of birds,

miniature explosions of flying fish, and, more exotically if less frequently,

by schools of joyous dolphins. Dolphins

always look to me as if they had just been let out of school rather than being

actually in it. Had my fate been a deep

sea existence with a choice, I should above all prefer to have been a

dolphin. I can’t believe there has ever

been a sad dolphin. The magnificent

grace, seemingly effortless power, and the visible ecstasy of their flight –

wingless but flight surely, in, out and over the waves – is music, mute, magic

and unforgettable. And if you have only

once seen a dolphin at close quarters, you will be able to imagine the “smile”

on his face and hear his song.

Then early

one fine morning – it was such a very fine morning – we looked out of the

porthole to find the ship was gliding into Table Bay under a sky of deep

cloudless blue, with the Mountain towering and curving behind it like a massive

welcoming mamma. It was so beautiful

that I did not even remember I had expected to be gliding towards the Harbour of

Colombo, saluting not Table Mountain, but Adam’s Peak from the porthole.

Before

disembarking we presented ourselves, following instruction, before three-eyed

officialdom, watching VIPs being whisked discreetly from the immigration and

passport centre queues, never dreaming that the day would come when short cuts

would appear for me also, not that we became VIPs – just habitués with good

S.A. friends.

Again we

marked the slightly wary glint in the blue eyes. I

managed to restrain myself until we met it yet again as we were making our exit

from Capetown for the homeward voyage.

Yes, we did get sea passages after all.

Nowadays, formalities for departing visitors seem to have been reduced to a very bare

minimum, but at that time we were apparently still of some interest to the

officials – I do not know why.

The

particular customs officer in question was not only blue-eyed. He was young, slim, devastatingly

handsome. He was also stern, which

somehow didn’t seem fitting in the circumstances.

“Have you

anything to declare?” he asked; and by his accent it was obvious that

Afrikaans came more fluently to his tongue than English.

“Yes, I

have.” I answered firmly in tones meant to be fraught with deeper meaning.

J. shocked

slightly and nudged me. The blue eyes gave me a startled look, then they narrowed suspiciously.

“I declare

that I have enjoyed my first visit to South Africa enormously and I hope to come back

again soon.”

There was a

slight pause while he decided whether or not I was making a mock of him. I smiled my most natural smile, which has

become a grand maternal one (several times) since then. He relaxed, and responded with the sort of

smile that is not only worth waiting for but worth working for too.

But that was

two months after an introduction to the Fairest Cape. As we stepped off the gangplank on to some

perfectly ordinary cement or concrete or whatever quaysides are made of, I

jumped gently on both feet, and said “J. we are actually here – we are in

Africa!”

This

performance caused another disembarking passenger who just managed to avoid

knocking me flat on my face, to give me a look which said clearly: “Stupid

clot! Where do you expect to be off of that ship?”

|

Record of one of the return voyages

for Isobel and Jeffrey |

We wended

our way to the SART Bureau in Adderley Street (Puff-Adderley)

wishing we had as many eyes as peacocks.

I wished I were invisible so that

I could stand and stare without being rude.

South Africans are a handsome race, or perhaps one should say a handsome

collection of countless races, and particularly attractive is the young

European variety. Each girl we saw that

first gloriously sunny day (and many other subsequent ones) in Capetown seemed

prettier than the last. What did juggle

me a little was to see so many young and less young matrons, not only lovely and

charmingly dressed, but also sporting hats, gloves and stockings as well. However, luckily for me, one of the advantages

of being a tourist is that whatever one wears or, almost does not wear, no one

gives you a second glance.

Later we

realized that Capetown observes a certain formality – or feels it ought to observe it –

which is notably absent in Durban for example.

A year or two later I was still rhapsodizing on these lives to a Durban

school teacher – this was before the onslaught of tight pants and mini-skirts.

“ – and they

wear such charming clothes,” I concluded.

“Well of

course,” Tim replied thoughtfully, “you must remember that girls in South Africa

dress purely for decoration. In Britain

you dress for survival, don’t you?”

We do.