A number of the Allisons

who settled across Northern Ireland became physicians. Hazlett Allison (1851-1925), named for his

mother Rachel Hazlett, was born at Drumnaha, the same farm that had been in the

Allison family for generations. He became

a doctor and joined the Indian Medical Service.

He and his wife Mary had three sons and one daughter. Their first child, Hazlett Samuel Allison

(1894-1917) was born at Fort St. George (now known as Chennai) in Madras (now

Tamil Nadu), India. Fort St. George was

the administrative seat of British power in India and was built in the 1600s as

the first British settlement in India.

It was rebuilt in the mid-1700s and is now used as an administrative building

for the state legislature of Tamil Nadu.

|

| Fort St. George |

In 1873, Hazlett

Allison joined the Indian Medical Service as a surgeon, arriving at Fort St.

George in 1874 where he took up his post.

He rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, distinguishing himself as a

Professor of Anatomy at the medical college and became a fellow at Madras

University in August 1892. In June 1891,

Hazlett married Mary Hunter Woods, and they both went to live in India. It was

while he was posted in Madras that Hazlett and Mary welcomed their first child,

Hazlett Samuel Allison, born in 1894. From

July 1901 to December 1903, when he retired, Lt-Col. Hazlett Allison was the

surgeon general at the hospital in Madras (records indicate the family had

already re-settled in Ireland in 1901 by the time of Lt.-Col. Allison’s

retirement).

Hazlett Samuel spent

his first years in India before his parents returned to their home in The

Shola, Portrush, Ireland in 1901. Noreen

Mullan, a local historian, has written an account of Hazlett Samuel Allison’s

life and notes that at the age of 10, young Hazlett entered school at Campbell

College Belfast. The school was still quite

new, having been established in 1894, and was at that time primarily a formal

boarding school, with significant grounds and facilities, located near the

Northern Irish Parliament at Stormont. He

graduated in 1911 and that same year entered Jesus College Cambridge.

By all accounts,

Hazlett Samuel was an athlete, demonstrating prowess in rugby and golf. While he didn’t continue in rugby while at

Cambridge, he did continue to indulge in his passion for golf. N.Mullan’s account includes a golfing

incident that made it into the local papers.

The incident took place in 1913 in the final round of the President’s

Cup, a foursome competition. The team

was reportedly Mr Lloyd Campbell / Mr H V Coates and Mr H S Allison / Mr R A

Cramsie. The local paper reported:

The players were all

square playing to the seventeenth (or gasworks) hole, approaching which the

ball driven by Mr Allison wedged between the wire netting, which is placed

round the green to prevent balls going out of bounds, and the top or guiding

wire of the fence. The local rule says

that a ball outside the fence is out of bounds, and the rules of golf on the

subject are that a ball is "out of bounds" when the greater part of

it lies within a prohibited area. In

this case the ball was exactly centred; and a diagram has been drawn by Mr

Vint, the secretary, showing the exact position of the ball, with explanatory

notes, to be forwarded to the golfing authorities for decision. If it is held that the ball was within

bounds, Mr H S Allison and Mr R A Cramsie would be the winners by one

hole. After the incident above described

two further holes were played, each of which were ties.

At both Jesus

College and at Campbell College, Hazlett Samuel was part of the Officer Training

Corps (OTC), which would not be unusual for students, and certainly not for

someone like Hazlett Samuel whose father was himself a member of the British

military.

In 1914, Hazlett

Samuel Allison graduated with his B.A. from Jesus College Cambridge. His intent was to follow his father in

medical studies, and he wrote his first exam for medical school the year of his

graduation - the same year the war broke out.

At the age of 20, having spent his formative years in Madras surrounded by soldiers, and training with the OTC since he began his

education in Ireland, Hazlett Samuel Allison must have felt duty-bound to

join up. He enlisted on August 8, 1914

and was given the position of Second Lieutenant to the Royal Irish Rifles (‘D’

Company, 7th Battalion). Before the end

of the year he rose to Lieutenant. His

Battalion was posted to the French theatre of war in December 1915. In April 1916 he had gained the rank of

Captain and that December, Major. At

that time, he was one of the youngest Majors in the Army.

In 1914, Hazlett

Samuel Allison graduated with his B.A. from Jesus College Cambridge. His intent was to follow his father in

medical studies, and he wrote his first exam for medical school the year of his

graduation - the same year the war broke out.

At the age of 20, having spent his formative years in Madras surrounded by soldiers, and training with the OTC since he began his

education in Ireland, Hazlett Samuel Allison must have felt duty-bound to

join up. He enlisted on August 8, 1914

and was given the position of Second Lieutenant to the Royal Irish Rifles (‘D’

Company, 7th Battalion). Before the end

of the year he rose to Lieutenant. His

Battalion was posted to the French theatre of war in December 1915. In April 1916 he had gained the rank of

Captain and that December, Major. At

that time, he was one of the youngest Majors in the Army.

His rise in the

ranks was due to extraordinary courage and initiative, evidenced by the war

diaries and by his mention in despatches.

On the night of June 27, 1916, the 7th Irish were in the

trenches in Hulluch, France. Then

Captain Allison and another officer, 2nd Lieutenant M.J. Hartery, left

the camp and crossed the enemy’s wire to look for gaps. Their inspection revealed no gaps, but a spot

along the wire which was thin and able to be cut. Soon enough they were seen and fired upon, so

returned to camp with their report. The

enemy fire at the camp was reportedly weak and erratic, so a couple of days

later, Captain Allison commanded another patrol which was mentioned in

Despatches in the London Gazette on 4 January 1917. The Despatch commended Capt. Allison for

gallant and distinguished service in the field.

The official record says:

Near Hulluch, on the

night of 31 July - 1 Aug, he was in charge of an enterprise against the German

trenches. Shortly after the return of his party, the enemy made a bombing

attack on our saps. Capt. Allison immediately returned to the saps and

organized a counter-attack, which not only drove off the Germans, but followed

them up and bombed them back into their own trenches. During the past nine

months Capt. Allison has repeatedly shown great courage and resource whilst

leading patrols, and has set a splendid example to all ranks.

|

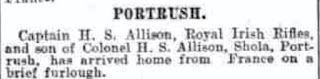

| Article from Weekly Telegraph November 25, 1916 p.7 |

There were five major offensives at Ypres, Belgium. The army was seeking to take high ground and eventually take back this northern part of France, Belgium and Holland. The attacks would ultimately lead to the battle at Passchendaele. By the summer of 1917 when Major Hazlett Samuel Allison and the Royal Irish Rifles marched in, the Battle for Messines was about to commence.

The war diaries of

the 7th/8th Battalion recount movements in and around

Ypres, through trenches, to small towns to train, bathe and be inspected, get

prepared for offensives, and be subjected to constant shelling and artillery

fire that was unpredictable in its intensity.

Over the course of that summer leading to the battle at Passchendaele, the

weather deteriorated and the trenches became soaked, the field mud, and any

effort at attack gained inches at best.

On May 16, 1917, Major

Allison left on leave, returning May 30 when his Battalion was stationed at

Butterfly Farm. Just two nights before, the Farm had been subjected to heavy shelling, resulting in two wounded

and one soldier suffering from shell shock.

At the end of May, the unit’s strength was 40 officers and 940 other ranks.

The first week of

June, the 7th Battalion was issued Order Number 118 (June 6, 1917). The Battalion was to be part of the Battle of

Messines:

Whilst moving to

assembly position and when finally in position, every care is to be taken to

avoid arousing the suspicions of the enemy.

Smoking, striking of matches, flashing of torches and unnecessary talking

are forbidden.

The Battle at

Messines was intended to draw German troops away from the embattled French forces

and capture German defences on the ridge that ran through Messines and

Wytschaete. This would allow the British

a high ground from which to command their attack on Passchendaele, and

ultimately drive the army up the coast to Holland. It was a first strike preparing for the Third

Battle of Ypres in July. In the Battle

of Messines, the troops were to use a creeping barrage, which is a slow moving

artillery attack which provides cover for infantry behind it. In this case, the attack would start with

mines.

The Royal Irish were

to provide Brigade Support on the right and left of the attack on Gil Trench (the

Mauve Line). They would take over in the

event the attacking 9th Royal Dublin Fusiliers became otherwise

engaged. Royal Irish were to move to a position

at Vierstraat Switch. Once the Mauve Line

was taken, they would need to work quickly to consolidate their line. Having received their orders, the Battalion

prepared for the assault. The evening of

June 6, the Battalion was inspected at their position opposite Wytschaete. They marched to their position opposite Vierstraat

Switch, arriving by 2 am. 3:10 am was zero

hour. The mines went up, artillery opened

fire and the attack commenced.

By 8 am, the

Battalion received orders to move to the Chinese Wall, which took them an hour

and a half, and they remained there through the day. The fighting was intense,

but the German defence had been devastated by the mines and shelling. The Irish Rifles as part of a larger force

were able to take their objectives as the remaining German forces eventually either

surrendered or retreated. On June 8, the

battalion relieved the 47th brigade on the Black and Blue lines and

installed their battalion headquarters in a dugout in Wytschaete Wood. The Battalion was later relieved and moved to

Vierstraat Switch with HQ at The Ribb.

It wasn’t until June

11, after four intense days of fighting, that the Battalion was withdrawn from

the line and marched to Clare Camp. Throughout

June, the Battalion engaged in the cycle of trench warfare: marching, billets,

parades, inspections, training, and fighting.

On June 29, they arrived at Rubrouk for much needed baths. At the end of June, the battalion strength

was 39 officers and 969 other ranks. The

Battalion had lost an officer when their HQ was hit with artillery fire.

The Commonwealth forces

had managed to take the Messines Ridge in June, but then started a long slog through

trenches with little gain. July was much the same as June, with weather getting

worse, affecting trenches and the ability to make any ground forward. On July 26, 1917, Major Allison and some other

officers left Camp Watou Area No 1 to reconnoitre the front. On July 30, the Battalion was getting ready as

corps reserve (order No 129). The Third

Battle of Ypres was about to start. This

battle was intended to move closer to Passchendaele by taking the ridges south

and east of Ypres. The Royal Irish were

in their ready position on July 31 at 11 p.m.

At 3:40 am the battle commenced.

|

| Excerpt of trench map showing Frost House and Frezenberg |

The battalion was attached to the 44th Infantry brigade for the attack. Under heavy fire, the Battalion was in

position on August 1 waiting for relief, when at 6 pm they heard that they

would not be relieved until the situation in front was “cleaner”. They received orders to stand and be ready to

hold the German front back. The commanding

officer understood that the Germans may have broken through north of Frost House.

The orders to remain

and hold the position continued through August 2. At 4 am that morning the Battalion was

ordered to send out guides to bring back the 47th Brigade from a

meeting point at Potijze Chateau. The

guides went out as ordered, but no battalion showed up for them to guide back. Finally, at 2:10 pm that day, the battalion

was ordered back Toronto Camp, arriving at 7:15 pm after three exhausting days

of fighting. But they were never far

from danger. After a rest and baths,

they marched to railways near Brandhoe and then continued on to Ecole. There was often artillery fire, and on August

7 they were heavily shelled. They arrived

at Frezenberg Redoubt to continuous bombardment. On August 8 the Battalion HQ was hit and

everyone who was in there at the time was either killed or wounded.

It was here, at

Frezenberg Redoubt, after a week of heavy fighting, marching, exhaustion and confusing

orders that Major Hazlett Samuel Allison of B company was killed – August 9, 1917. He was buried nearby, but the location of his

grave was never found again. His company

had to leave him behind when, on August 15, they headed to the trenches to join

in the attack on Frezenberg Ridge.

The Passchendaele Archives

describes Major Allison’s death:

On 7 August 1917 the

7th Battalion Royal Irish Rifles (48th Brigade, 16th Division) marched to the

frontline and relieved the 2nd Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers. D Company was

positioned on the left of the Ypres-Roulers Railway, near Frezenberg. The next day

the Germans shelled the frontline during the whole day. They hit the battalion

Headquarters, killing or wounding all the runners and observers. On 9 August

1917 Major Allison was killed, probably by a shell. He was buried near to the

place where he was killed, but afterwards his body was never found.

|

| excerpt from Battalion war diaries showing entry for Major Allison's death |

Before the Third

Battle of Ypres, at the beginning of August, the Battalion counted 36 Officers

and 862 other ranks. By the end of the

month, there were 18 officers and 606 other ranks. The month had been devastating not just for

Major Allison, but for so many who died in the fighting: the 7th Battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles was not the only one that had suffered significant loss: the official total of losses for British Commonwealth forces numbered greater than 244,000.

Major Allison was awarded

the 1914-15 Star, the British War Medal, and Victory Medal, all of which were

sent to his father at The Sholes, Portrush, Ireland on September 12, 1919.

Hazlett Samuel Allison

did not live to see the victory at Passchendaele, which occurred in November,

but his contribution to this fight is commemorated at the Menin Gate.

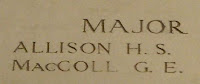

|

| Menin Gate Ieper. Above right, inscription on Panel 40. |

Every evening at the

Menin Gate in Ieper, The Last Post is sounded in memory of the thousands whose

names are engraved on the panels inside the memorial. These are names of those without graves who

died between October 1914 and October 1918 in Belgium, including Major H.S.

Allison.

Major Allison is also remembered at memorials through Jesus College Cambridge, Irelands War Memorial Records 1914 – 1918, Portrush War Memorial, Holy Trinity Church, Portrush, Campbell College, Belfast, and at the Family Grave, Ballywillan (Old) Graveyard.

On this Remembrance

Day 2019, I will remember Major Hazlett Samuel Allison of the 7th

Battalion, Royal Irish Rifles – born in India, excelled in College, a keen

rugby player and talented and committed golfer, and an extraordinary officer.

|

| From UK, De Ruvigny's Roll of Honour, 1914-1919, p.5 |

References and acknowledgments:

Thanks to Noreen

Mullan for her excellent research and some photos (used with permission), and

to Dr. James Allison for his contributions.

Trench maps National

Library of Scotland. https://maps.nls.uk/

De Ruvigny’s Roll of

Honour, 1914-1919 p.5

Original War Diary 7th

Battalion Royal Irish Fusiliers

Images of Menin Gate

used in this article are originals.

Please seek permission to re-use.

Image of HS Allison

memorial at Menin Gate: http://www.instgreatwar.com/page17.htm

Mention in Despatch

available at: https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/5beca90e-bb8b-4ae7-86fd-16c6edc893e2

Jon Sandison’s article

about his visit to the Menin Gate:

http://www.scotlandswar.co.uk/pdf_At_The_Menin_Gate.pdf

Menin Gate in

photos: http://thebignote.com/2014/11/03/the-menin-gate-memorial-to-the-missing/